The Wildlife Council Approach To Protecting the North American Model of Conservation

Persistent and seemingly irreversible declines in hunter numbers have led state agencies to spend ever increasing amounts of slowly diminishing resources on hunter recruitment, reactivation, and retention (so-called ‘R3’). Bag liberalizations, changes to season structure and legal weapons categories, and a variety of innovative mentoring schemes for ‘adult onset’ hunters and under-represented groups are all examples of these efforts.

Unfortunately, there’s not much evidence that R3 effectively ‘moves the needle’. Almost 50% of those that complete hunter education stop buying hunting licenses within 2 years. Today, only 4.6% of Americans self-identify themselves as hunters.

According to the demographers, American cultural and recreational preferences are shifting, and the evidence now strongly suggests that R3 isn’t likely to produce much course correction. New strategies to protect hunting, trapping, and angling are needed, and the Nimrod Society (https://nimrodsociety.org) and Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation (https://congressionalsportsmen.org) are taking a different approach.

Overall, these organizations aim is to change the way that the non-hunting/trapping/angling public thinks and feels about these activities instead of trying to increase participation.

At Hillsdale College, the Nimrod Society has established the Nimrod Education Center, where the over-arching theme is essential importance of conservation, what Gifford Pinchot defined as “the greatest good to the greatest number for the longest period of time”.

The Hillsdale Center:

-

-

- offers coursework and scholarships tied to the North American Model of Fish and Wildlife Conservation and its’ legal framework

- is exploring the development of relevant coursework for Hillsdale network of K-12 Classical Charter Schools and the development of a free on-line Hillsdale course on the history of conservation and the importance of the North American model.

-

Even more important, the Nimrod Society, in partnership with the Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation, is prioritizing the establishment of state-based wildlife councils that develop marketing strategies to influence the opinions and attitudes of those that will never hunt, trap, or fish.

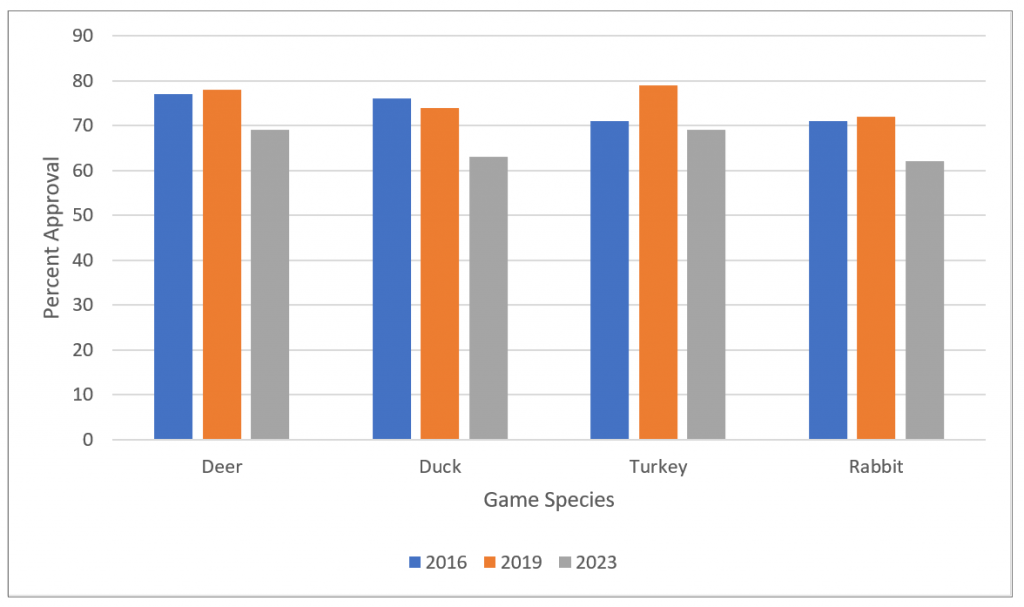

A 2023 national survey by Responsive Management and the Outdoor Stewards of Conservation Foundation (https://www.outdoorstewards.org/americans-attitudes-towards-fishing-target-shooting-hunting-and-trapping/) reports that public disapproval of legal regulated hunting is accelerating. Just between 2019 and 2023, support for deer hunting dropped 8.5%.

Although the reasons aren’t clear, the survey authors speculate that steep declines in public support for hunting reflect the broader political climate that pits stereotypes of ‘anti-gun’, ‘anti-hunting’ urban and suburban Democrats against ‘gun-loving’, ‘pro-hunting’ rural Republicans.

If this partisan explanation is true, then there’s reason to be optimistic. Michigan, a ‘battleground state’, is pursuing a nonpartisan approach that seems to be bearing fruit. One reason for not just stable but increasing support for hunting is the Michigan Wildlife Council (MWC).

The MWC is a nine-member group appointed by the Governor and funded by $1 from the sale of every base hunting and all-species fishing license. The sole purpose of the Council is strategic marketing, education, and outreach to the non-hunting, non-fishing, non-trapping public about:

-

-

- The value of hunting, trapping, and fishing as wildlife management tools,

- The essential importance of license dollars to habitat, wildlife, and conservation work,

- The contributions of consumptive recreation to Michigan’s economy,

- The roles that hunting, trapping, and fishing play as parts of Michigan’s cultural heritage.

-

MWC was established in 2013. When the group and its’ contractor (Gud Marketing) conducted its’ first statewide (baseline) survey in 2015, 62% of Michiganders indicated that they approved of hunting for food, to protect agricultural production, manage populations or safeguard human health or safety.

However:

-

-

- 39% didn’t think hunters were responsible people.

- 42% didn’t think or didn’t know whether hunters followed regulations.

- 61% didn’t think or didn’t know whether management was important for healthy wildlife populations.

- 44% believed or didn’t know whether legal regulated hunting led to species extinctions.

-

In response, the MWC initiated targeted marketing campaigns in selected markets where disapproval and/or misinformation was measurably the greatest.

Today, 84% of Michiganders approve of hunting, 67% have favorable opinions about hunters (an increase of 14%), and 89% agree that hunting is important to Michigan’s culture. Eighty-seven percent agree that hunting is a valuable management tool and 78% agree that wildlife and habitat work are largely funded through the sale of hunting and fishing licenses.

The Colorado Wildlife Council has experienced similar success. Today, 80% of registered voters support legal, regulated hunting and fishing, 90% agree it’s ok for others to hunt in accordance with Colorado hunting laws and regulation and 90% say hunting and fishing should be legal.

Looping back to the national perspective, it wouldn’t be surprising if the first impulse of some would be to resist public marketing decoupled from R3. Undoubtably, there will be concerns that Wildlife Councils will become just another way for new constituencies and stakeholders to make requests of an already over-tasked fish and wildlife workforce.

Nonetheless, 95.4% is a bigger number than 4.6%, and that means that the future of hunting depends more on the attitudes of an increasingly diverse and non-rural public than on the attitudes of hunters.

Public opinion matters when it comes to legislation and referenda. Nationally, public attitudes toward consumptive use aren’t improving. To maintain traditions and keep hunting available to everyone, it’s past time to consider new approaches with measurable benefits that include more positive public attitudes towards the conservation benefits of hunting to wildlife and for outdoor recreation in general. Wildlife Councils are one way to accomplish this increasingly important goal.